- Drug Topics September 2023

- Volume 167

- Issue 08

Review of FDA Approvals for Pediatric Obesity Management

GLP-1 receptor agonists, used to manage diabetes, are now being used for obesity in children and adolescents.

Pediatric obesity affects more than 14 million children and adolescents, equivalent to 1 in 5 children in the United States. Obesity prevalence continues to increase in the pediatric population. Certain racial and ethnic minority groups have seen a greater rise, with Hispanic individuals having the highest prevalence of obesity at 26.2% followed by non-Hispanic Black individuals at 24.8%. Biological sex does not seem to play a role in the risk of obesity; the prevalence of obesity is similar between boys (20.9%) and girls (18.5%).1

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) defines obesity as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for age and sex.2 The CDC reported childhood obesity prevalence data from 2017 to 2020 at 12.7% among children aged 2 to 5 years, 20.7% among children aged 6 to 11 years, and 22.2% among individuals aged 12 to 19 years.1

Risk factors for development of childhood obesity include modifiable factors (eg, physical activity levels, certain medications, sleeping patterns) and nonmodifiable factors (eg, low socioeconomic status, certain disease states, specific racial and ethnic minority groups).3 Pediatric obesity has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension, asthma, polycystic ovary syndrome, type 2 diabetes, low self-esteem, depression, and eating disorders.4,5

Caregivers can help prevent childhood obesity by instituting the following changes with their children: establishing a daily routine; adhering to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s age-based sleep recommendations; providing balanced meals of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, healthy fats, and protein; limiting screen time to the AAP’s age-based recommendations; and promoting approximately 300 minutes of physical activity weekly.1,6,7 Caregivers should encourage a balanced diet of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, protein, and some fats. Limiting fruit juices and adding water to every meal should also be encouraged. The Kid’s Healthy Eating Plate, created by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, can be offered to caregivers as a guide for creating balanced meals.8

Clinicians should query caregivers about access to nutritious foods, time available to prepare meals, who is preparing the meals, and current support systems in place. Increasing accessibility, affordability, and subsequent enrollment into physical activity–based programs for children can help combat obesity secondary to a lack of physical activity. Organized sports teams and outdoor activities often come to mind; however, indoor physical activity within the home or school or via a community group should be offered to children limited by the safety of their neighborhood. Referring social workers for families challenged by living in high-crime areas is a great resource to employ for increased support, connection, and guidance as warranted.9

Treatment

First-line therapies for obesity management recommended by the AAP are motivational interviewing and creation of personalized treatment plans, which include dietary modifications, increased physical activity, behavioral modifications, and psychoeducation.4 Pharmacological treatment may be considered adjunctively when nonpharmacological therapy alone does not achieve the desired results.4 Thus far, the FDA has approved 4 medications for chronic weight management in pediatric populations: orlistat (Xenical),10 phentermine and topiramate extended-release capsules (Qsymia),11 liraglutide (Saxenda),12 and semaglutide (Wegovy).13 This review will focus on the newly approved glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs).

GLP-1 RAs bind to the GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas, brain, and gastrointestinal tract to stimulate insulin release. Additionally, GLP-1 RAs delay gastric emptying, which in turn reduces food intake and promotes a feeling of fullness.14

The FDA granted approval for the first GLP-1 RAs in April 2005 for blood glucose control in adult patients with type 2 diabetes.14 The medication class contains dulaglutide, exenatide, semaglutide, liraglutide, and lixisenatide. Of these, liraglutide and semaglutide are FDA approved for pediatric weight loss.15,16 In December 2020, liraglutide received approval as an adjunctive agent to lifestyle modifications for chronic weight management in pediatric patients 12 years or older with body weight greater than 60 kg and an initial BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.15

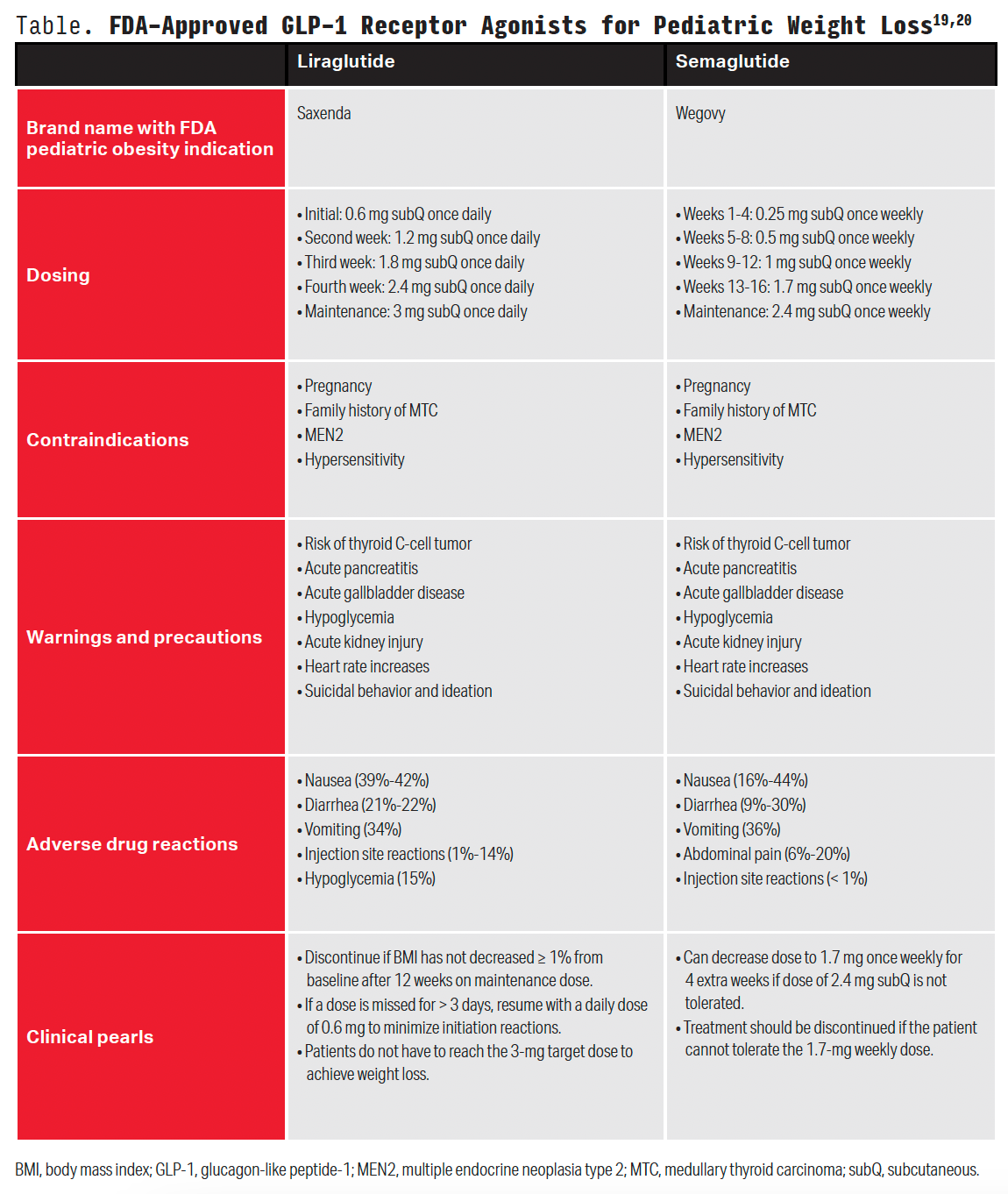

In December 2022, the FDA approved semaglutide as an adjunctive agent to lifestyle modifications for chronic weight management in pediatric patients 12 years or older with an initial BMI equal to or greater than the 95th percentile standardized for age and sex.16 The phase 3, interventional STEP TEENS clinical trial (NCT04102189) showed semaglutide was superior to placebo, with a change in BMI percentage by week 68 (a 16.1% reduction with semaglutide vs 0.6% increase with placebo). Patients commonly experienced nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and abdominal pain during the study. Discontinuation of the trial regimen occurred in 5% of patients in the semaglutide group and 4% in the placebo group, most commonly because of gastrointestinal events.15 Liraglutide was evaluated in a placebo-controlled, 56-week clinical trial (NCT04102189). Results demonstrated a 2.65% reduction in body weight with liraglutide vs a 2.37% increase with placebo. Gastrointestinal events were common and were the most common reason for regimen discontinuation (10% vs 0% with liraglutide vs placebo).16 Of note, exenatide has shown to significantly reduce BMI in adolescent patients with severe obesity compared with placebo; however, exenatide is not currently FDA approved for use in the pediatric population for this indication.17 Medication information for liraglutide and semaglutide (Wegovy) can be found in the Table.13,20

GLP-1 RAs are administered via a subcutaneous injection in the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm. Patients and caregivers should be counseled on appropriate medication preparation and injection techniques. Liraglutide and semaglutide products come packaged in ready-to-use pens, whereas exenatide formulations require product manipulation prior to administration, necessitating additional patient education.13,20

Findings from studies within the adult population have shown semaglutide results in significantly greater weight loss vs liraglutide; however, no current studies are examining superiority between the GLP-1 RAs in the pediatric population.21,22 More research is needed to better categorize the expected BMI reduction with each agent. Findings from available studies show up to 76% and 43.3% of adolescent patients reaching BMI reduction of 5% or more with semaglutide and liraglutide, respectively, within the designated study periods.23,24

As mentioned, GLP-1 RAs serve as an adjunctive agent to lifestyle modifications. A meta-analysis conducted by Ryan et al revealed a synergistic effect between the combined use of GLP-1 RAs and lifestyle interventions, which resulted in greater reductions in blood pressure levels, hemoglobin A1c levels, and weight compared with using GLP-1 RAs alone.25 Other considerations when choosing between products may include cost and insurance formulary. Patient assistance programs and savings offers are available for both liraglutide and semaglutide through the manufacturer to offset high co-pays and ease private pay costs.

Conclusion

First-line therapies for the management of pediatric obesity focus heavily on nonpharmacological measures. Pharmacological treatment can be offered adjunctively when desired results are not achieved through nonpharmacological measures alone. Semaglutide and liraglutide are 2 FDA-approved medications for this indication that are generally well tolerated in the pediatric population.

This article originally appeared in the July issue of

Caitlyn Bradford, PharmD, is an assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy at Saint Joseph’s University in Pennsylvania.

Wade Tung, Natalie Catalan, and Justine Magalona are PharmD candidates at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy at Saint Joseph’s University.

Danielle M. Alm, PharmD, is an associate professor of clinical pharmacy at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy at Saint Joseph’s University.

References

1. Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey 2017–March 2020 prepandemic data files— development of files and prevalence estimates for selected health outcomes. CDC. June 14, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://stacks.cdc. gov/view/cdc/106273

2. Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022060640. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-060640

3. Chi DL, Luu M, Chu F. A scoping review of epidemiologic risk factors for pediatric obesity: implications for future childhood obesity and dental caries prevention research. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(suppl 1):S8-S31. doi:10.1111/jphd.12221

4. Smith JD, Fu E, Kobayashi MA. Prevention and management of childhood obesity and its psychological and health comorbidities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020;16:351-378. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-100219-060201

5. Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):251-265. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.017

6. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020-2028. doi:10.1001/ jama.2018.14854

7. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):785-786. doi:10.5664/ jcsm.5866

8. Kid’s healthy eating plate. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 2015. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/ nutritionsource/kids-healthy-eating-plate/

9. Ayala-Marín AM, Iguacel I, De Miguel-Etayo P, Moreno LA. Consideration of social disadvantages for understanding and preventing obesity in children. Front Public Health. 2020;8:423. doi:10.3389/ fpubh.2020.00423

10. Xenical. Prescribing information. H2-Pharma LLC; 2022. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://xenical.com/pdf/PI_Xenical-brand_FINAL.PDF

11. Qsymia. Prescribing information. VIVUS LLC; 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/ label/2022/022580s021lbl.pdf

12. Saxenda. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk; 2022. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf

13. Wegovy. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk; 2023. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/wegovy.pdf

14. Zhao X, Wang M, Wen Z, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists: beyond their pancreatic effects. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:721135. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.721135

15. Sheahan KH, Wahlberg EA, Gilbert MP. An overview of GLP-1 agonists and recent cardiovascular outcomes trials. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96(1133):156-161. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-137186

15. FDA approves weight management drug for patients aged 12 and older. News release. FDA. December 4, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2023. https:// www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-weight-management-drug-patients-aged-12-and-older

16. FDA approves once-weekly Wegovy injection for the treatment of obesity in teens aged 12 years and older. News release. Novo Nordisk. December 23, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.novonordisk-us. com/media/news-archive/news-details.html?id=151389

17. Kelly AS, Rudser KD, Nathan BM, et al. The effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapy on body mass index in adolescents with severe obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(4):355-360. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1045

18. Saxenda. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk; 2022. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf

19. Wegovy. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk; 2023. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/wegovy.pdf

20. Murvelashvili N, Xie L, Schellinger JN, et al. Effectiveness of semaglutide versus liraglutide for treating post-metabolic and bariatric surgery weight recurrence. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(5):1280-1289. doi:10.1002/oby.23736

21. Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, et al; STEP 8 Investigators. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(2):138-150. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23619

22. Weghuber D, Barrett T, Barrientos-Pérez M, et al; STEP TEENS Investigators. Once-weekly semaglutide in adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(24):2245-2257. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2208601

23. Kelly AS, Auerbach P, Barrientos-Perez M, et al; NN8022-4180 Trial Investigators. A randomized, controlled trial of liraglutide for adolescents with obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1916038

24. Ryan PM, Seltzer S, Hayward NE, Rodriguez DA, Sless RT, Hawkes CP. Safety and efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in children and adolescents with obesity: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2021;236:137- 147.e13. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.05.009

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Pharmacyover 2 years ago

Assessing and Treating Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancyover 2 years ago

Dance With the Girl That Brung Yaover 2 years ago

Gut Health Has Impact on the Skinover 2 years ago

Biologics Offer Great Results in Treating Psoriasis—At a Costover 2 years ago

In A Post-Dobbs World, Pharmacists Still Face Uncertaintyover 2 years ago

How AI Can Improve Controlled Substance SecurityNewsletter

Pharmacy practice is always changing. Stay ahead of the curve with the Drug Topics newsletter and get the latest drug information, industry trends, and patient care tips.