Evaluating the Safety of Tetracycline Use During the First Trimester of Pregnancy

As “therapeutic orphans,” pregnant women and their health care providers must balance the benefits of treatment with the risk of fetal harm.

Maternal use of tetracycline antibiotics during the first trimester of pregnancy did not increase the risk of major congenital malformations in newborns, according to research results published in JAMA Network Open.1

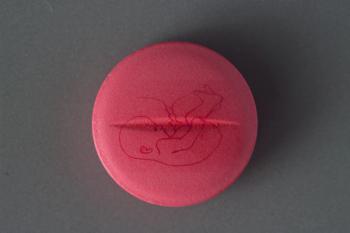

Due to its activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, drug-resistant bacteria, and parasites, tetracycline antibiotics are widely used to treat multiple conditions, including common bacterial, sexually transmitted, skin, and atypical respiratory infections.

In women who are

Due to the limited availability of data, researchers sought to evaluate the association between tetracycline exposure during the first trimester and the risk of major congenital malformations.

Investigators conducted a population-based cohort study using data on all singleton newborns born between July 1, 2006, and December 31, 2018, from the Swedish health and population registers. First trimester exposure to tetracyclines was defined as at least 1 prescription filled by the mother between the first day of the last menstrual period and 97 days gestation; infants born to mothers who did not fill a tetracycline prescription during the first trimester of pregnancy were considered unexposed.

READ MORE:

A total of 1,245,889 infants were eligible for study inclusion (51.4% boys), of whom 0.5% were exposed to tetracyclines during the first trimester. When compared with unexposed infants, those in the exposure group were more likely to be born in earlier calendar years: 32.5% of infants born between 2006 and 2009 had tetracycline exposure, compared with 18.3% of those born between 2016 and 2018. Mothers of tetracycline exposed infants were also in either the youngest or oldest age group, had diagnosed substance use disorders, smoked during early pregnancy, and used prescription drugs.

To account for confounding, investigators used propensity score matching; after this matching, the cohort included 69,656 infants, of whom 6340 were exposed to tetracyclines. Within the exposure group (52.4% boys), 78.3% were exposed to doxycycline, 18.9% were exposed to lymecycline, 2.8% to tetracycline, and 0.2% to oxytetracycline.

In the tetracycline exposure group, prevalence of major congenital abnormalities was 39.75 cases per 1000 infants (95% CI, 35.14-44.93) compared to 38.76 cases per 1000 infants in the unexposed group (95% CI, 37.27-40.30), totaling 252 and 2454 cases in each group, respectively.

Major congenital abnormality risk did not differ between groups (relative risk [RR], 1.03; 95% CI, 0.90-1.16). Exposure to tetracyclines was not associated with an increased risk for either 10 of 12 major congenital malformation subgroups or any of the 16 individual major congenital malformations analyzed. However, higher relative risks were noted for nervous system and eye abnormalities (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 0.98-3.78 and RR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.07-2.91, respectively).

Sensitivity analyses were also performed; these analyses applied a stricter outcome definition and required at least 2 specialist outpatient care visits with major congenital malformation diagnoses. In these analyses, prevalence of nervous system and eye anomalies were lower than compared with the main analysis (RR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.27-5.51 and RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.65-2.83, respectively).

Over an extended follow-up period, the prevalence of nervous system and eye anomalies were 1.6-fold and 1.5-fold higher than the main analysis in the unexposed group.

When analyzing the data by specific drug, relative risks for any major congenital malformations were 1.07 for doxycycline only, 0.83 for lymecycline only, and 0.78 for tetracycline or oxytetracycline only.

Study limitations include the potential for selection bias, exclusion of other oral tetracyclines such as minocycline or intravenous tetracyclines such as tigecycline, a lack of data on inpatient antibiotic use and information on actual intake or timing of use, among others.

“First trimester tetracycline exposure was not associated with increased risks of [major congenital malformations],” the researchers concluded, adding that additional studies must be conducted to rule out potential risks.

In an invited commentary,4 John N. van der Anker, MD, PhD, of the division of clinical pharmacology at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC, noted that this study is “considerably larger (almost 4-fold) than earlier reports in terms of the number of exposed infants and documented cases,” while also covering a broader range of congenital malformation subgroups and individual major congenital malformations. But despite the positive aspects of this research, “it is still impossible to reach a definitive conclusion regarding the safety of tetracyclines during pregnancy,” van der Anker wrote.

“This lack of necessary knowledge for the optimal use of doxycycline or any of the other tetracyclines during pregnancy all boils down to the fact that pregnant persons still need to be viewed as therapeutic orphans,” he continued. Historically, clinical trials have excluded both pregnant individuals, as well as individuals with child-bearing potential, due to potential harms to the fetus. However, well-intentioned, this exclusion has led to significant information gaps “that make prescribing drugs for pregnant individuals with preexisting illnesses or new-onset disorders difficult and potentially dangerous” for both those who are pregnant and their fetuses.

Until additional data are available—including participation in clinical drug trials, global registries to document potential adverse events, and active surveillance systems—health care providers and pregnant individuals must weigh the benefits of treatment against potential fetal risks, van den Anker concluded.

READ MORE:

References

Nakitanda AO, Odsbu I, Cesta CE, Pazzagli L, Pasternak B. First trimester tetracycline exposure and risk of major congenital malformations. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e244055. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.45055

Mansour O, Russo RG, Straub L, et al. Prescription medication use during pregnancy in the United States from 2011 to 2020: trends and safety evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;231(2):250.e1-250.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2023.12.020

Shutter MC, Akhondi H. Tetracycline. Stat Pearls. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed November 14, 2024.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549905 Van den Anker JN. Use of tetracyclines during the different stages of pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(11):e2447322. Doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.47322

Newsletter

Pharmacy practice is always changing. Stay ahead of the curve with the Drug Topics newsletter and get the latest drug information, industry trends, and patient care tips.