Balancing Risks and Rewards: Are Alzheimer Disease Treatments Worse Than the Illness?

How can current Alzheimer disease treatments be used to best treat patients living with the disease?

The recent approval of aducanumab caused an uproar: Was it approved too soon? What long-term effects will the treatment have? Is the cost worth it? Are we doing enough to address Alzheimer disease (AD)? As we grapple with these issues, the problem of AD continues to swell; more than 6 million Americans are living with the disease, and this number is projected to rise to nearly 13 million by 2050.1 AD will kill 1 in 3 affected seniors, and is more deadly than breast cancer and prostate cancer combined.1 What are the available and upcoming AD treatments and how can you utilize them to best serve your patients?

Currently Available Treatments

Although

Aducanumab (Aduhelm). You have heard about it—the amyloid-β–directed antibody indicated to treat mild AD that received FDA approval in June 2021, to the surprise of many, including some Psychiatric Times™ contributors.2 At the time, it was the first new treatment approved for AD since 2003. It was also the first drug on the market that targeted the underlying disease pathophysiology rather than symptoms.

Although patient groups applauded the approval, experts recommended caution; an FDA independent advisory committee even preemptively voted against approval in November 2020.3

Investigators evaluated aducanumab’s efficacy in 3 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging studies involving a total of 3482 participants with AD.4 Patients receiving the treatment had significant dose- and time-dependent reduction of amyloid-β plaque; however, data did not demonstrate aducanumab slowed cognitive decline, and there is no evidence to suggest it restores cognitive function.

“The issue is whether the clinical effects of these new drugs have a meaningful impact on patients and families,” said Gary W. Small, MD, chair of psychiatry, Hackensack University Medical Center, and behavioral health physician in chief, Hackensack Meridian Health, New Jersey.

Furthermore, although aducanumab is easily administered intravenously via a 45- to 60-minute infusion once every 4 weeks, access and insurance coverage are extremely limited and the price tag is hefty; the original estimated annual cost of aducanumab was $56,000,5 but Biogen recently halved that price to $28,200.6

Lecanemab (Leqembi). This monoclonal antibody is the second-ever treatment intended to attack the root of the disease and slow cognitive decline. It was approved under the FDA’s accelerated pathway based on phase 2 trial data, which showed that lecanemab decreased brain plaques in 856 study participants.7 A recent phase 3 trial, Clarity AD, found that it slowed cognitive decline by 27% over 18 months of treatment.8

Lecanemab is infused intravenously, enters the patient’s brain, and clears away amyloid plaques—which may cause cognitive impairment in AD.

The most common adverse effect is an infusion-related reaction, seen in 26.4% of participants and 7.4% in the placebo group in the Clarity AD trial. Of these reactions, 96% were mild to moderate and 75% happened after the first dose.9 However, at least 2 participants in the phase 3 trial taking lecanemab died after brain bleeds or swelling, and its label will include a warning about developing amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. Furthermore, any patient taking lecanemab should have 3 MRIs in the first 6 months of treatment to ensure no adverse effects develop.10

“This is the first time we have found unequivocally positive results for a therapy that may slow the course of Alzheimer disease. I think these results already demonstrate a meaningful benefit over 18 months,” Christopher H. van Dyck, MD, lead author on the study, told Psychiatric Times™. “But what we next want to know is whether earlier intervention and longer treatment can produce a larger benefit. The AHEAD trial is already well under way and will determine whether administration of the drug to asymptomatic individuals with elevated brain amyloid accumulation might preserve cognitive health even more.”

The annual price tag estimate for lecanemab is slightly lower than its predecessor aducanumab, ringing in with a cost of $26,500 per year.11

With the recently published data from the Clarity AD trial, Eisai intends to file a supplemental biologics license application to the FDA for approval under the traditional pathway soon.12

Galantamine (Razadyne). Approved by the FDA in 2001, this acetylcholinesterase inhibitor enhances cholinergic function by increasing the availability of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft through reversible, competitive, and selective inhibition of cholinesterase, thus blocking hydrolytic degradation of acetylcholine.13 It comes as an extended-release capsule and an oral liquid. As galantamine is a symptomatic treatment, it will not modify the underlying progression of the disease, but it can help improve cognition, daily functioning, and behavior.

The National Institutes of Health recommends regular follow-up and gradual titration of the dosage to assess efficacy and safety of the dose for the patient, as well as checking for drug-to-drug interactions.14 As to price, galantamine averages around $145 for 60 tablets of 4 mg each.15

Rivastigmine (Exelon). A cholinesterase inhibitor, rivastigmine is used in patients with AD and Parkinson disease and was approved by the FDA in 1997. Rivastigmine, unlike other cholinesterase inhibitors, has been shown to reversibly bind and inhibit both acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, causing an overall increase in acetylcholine.16

It comes as a capsule, oral liquid, and transdermal patch. The main adverse effects are gastrointestinal, primarily nausea and vomiting. One study found rivastigmine to be the drug with the highest rate of gastrointestinal adverse effects.17 The average retail price is $466 for 30 transdermal patches (4.6 mg/d) or $175 for 60 capsules of 1.5 mg.18

Donepezil (Aricept). Although this acetylcholinesterase inhibitor does not alter the progression of AD, it can improve cognition and behavior. Approved by the FDA in 1996, donepezil binds reversibly to acetylcholinesterase and inhibits the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, which enhances cholinergic transmission. It can take up to 15 days to reach steady medication level. Again, the main adverse effects are gastrointestinal.19 It is available as an oral film-coated tablet and an orally disintegrating tablet. The average retail price for 30 tablets of 10 mg is $94.20

However, to avoid the adverse gastrointestinal effects, Corium created the donepezil transdermal system (Adlarity), which received FDA approval in March 2022. The patch, applied once a week, continuously delivers donepezil through the skin. As it provides stable dosing for 7 days, it may be more practical for patients who cannot reliably take daily oral donepezil because of impaired cognition. But patches may take longer to work compared with tablets; achieving steady medication level can take up to 22 days. It is approved for 5-mg/d or 10-mg/d formulations.21 The average retail price for 4 patches of 5 mg is $545.22

The Pipeline

“This is a very exciting and extremely important time in Alzheimer research, treatment, and care. A diverse pipeline of potential new treatments, and eventually combination therapies, presents an unprecedented era of hope for the Alzheimer and dementia community,” said Alzheimer’s Association Chief Science Officer Maria C. Carrillo, PhD.

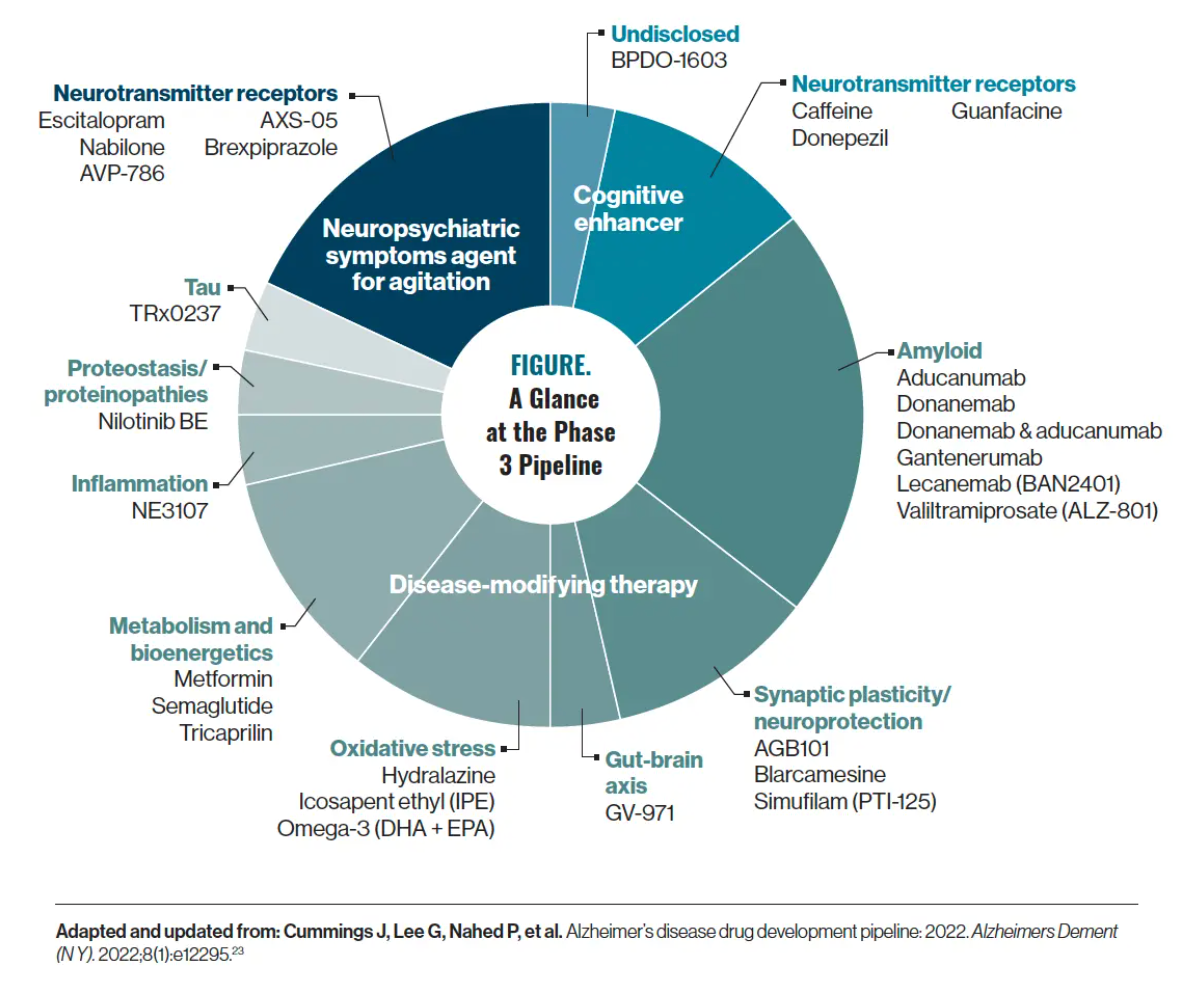

In the AD pipeline, amyloid is the most common target. Using information gathered from ClinicalTrials.gov, there are approximately 28 drugs in phase 3 of the pipeline for AD, and 21 of them are disease-modifying therapies (Figure).23 Now, although amyloid is the predominant research focus, a few recent phase 3 trial fails have shaken that certainty; both monoclonal antibodies targeting amyloid, gantenerumab and solanezumab, recently failed to prove clinical efficacy in phase 3 trials.24,25

Although these new options are exciting, there should still be a modicum of caution, according to Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, MS, DFAPA, DFAAGP.

“There may be new medications coming down the pipeline for the treatment of individuals with AD, but clinicians should continue to follow good clinical practice of obtaining a thorough, comprehensive mental status examination; objective, structured cognitive examination; a focused physical examination; appropriate laboratory work-up; and neuroimaging studies to diagnose cases of AD,” Tampi told Psychiatric Times™. “We can incorporate the new medications into the treatment plans of individuals with AD once we have a better understanding of their benefits and risks.”

With that in mind, here is a look at what is up and coming.

Donanemab. This monoclonal antibody treatment that acts against the amyloid-β protein is undergoing a phase 3 clinical trial to demonstrate its efficacy. In January 2023, the FDA decided not to grant donanemab accelerated approval; data from the phase 3 trial will be submitted later this year for full approval.

Notably, in the coprimary outcomes of the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 4 study, brain amyloid plaque clearance—which investigators defined as achievement of brain amyloid plaque levels less than 24.1 Centiloids—was achieved in 37.9% of participants taking donanemab (25 of 66) compared with 1.6% of participants taking aducanumab (1 of 64) at 6 months. Additionally, donanemab reduced brain amyloid levels by 65.2% from baseline, compared with 17.0% for aducanumab at 6 months.26

“The TRAILBLAZER study was a landmark study in our space,” said Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. “We have never had disease-modifying agents for Alzheimer disease, and now we are starting to see these come to fruition—hopefully, at some point soon, for full FDA approval. This is just the dawn of a new era, and a first series of drugs in this one class.”

Blarcamesine. In early December 2022, it was announced that blarcamesine—a small molecule activator of the σ-1 receptor—met primary and key secondary end points in a phase 2b/3 study evaluating mild cognitive impairment in patients with AD. This randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study enrolled 509 participants for over 48 weeks. Results found that participants treated with blarcamesine were 84% more likely to have improved cognition than placebo-treated participants, as measured by Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive subscale score change of –0.50 points or better from baseline to end of treatment. Additionally, those treated with blarcamesine were 167% more likely to improve function compared with placebo.27 The data from this study will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal. ATTENTION-AD, an open-label extension study, will continue to follow participants over a 96-week period.

Blarcamesine is also under development for several other conditions, such as Angelman syndrome, fragile X syndrome, infantile spasms, gait abnormality, Parkinson disease dementia, tuberous sclerosis, Rett syndrome, and more. It is available in intravenous and oral administration.28

Treating Behavioral Issues

Although it is best to address agitation through nonpharmacological means first, there are circumstances in which medication might be warranted. Psychotropics like antipsychotics can be used to treat agitation, but they can have serious adverse effects. Some experts argue that no current pharmacological interventions for agitation in AD possess benefits that outweigh their risks,29 but researchers are investigating new avenues for treating behavioral issues.

AXS-05. This combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion is being investigated for the treatment of agitation in patients with AD. AXS-05 was granted FDA breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of AD agitation in June 2020.

“At present, there are no FDA-approved treatments for agitation associated with dementia. Instead of managing agitation on an as-needed basis with ‘prn’ dosing, daily dosing of AXS-05 has the potential of preventing agitation over time, and thus is a proactive approach rather than a purely reactive strategy,” Leslie L. Citrome, MD, MPH, one of the primary investigators, told Psychiatric Times™.

Data suggest AXS-05 significantly delayed time to relapse of agitation versus placebo. In the ACCORD study of 178 participants, clinicians reported agitation improvement in 66.3% of patients at week 2 and 86.3% of patients at week 5 after treatment with AXS-05.30 Somnolence and dizziness were the most common adverse effects, reported in at least 5% of study participants.31

BXCL501 (Igalmi). This orally dissolving thin film formulation of dexmedetomidine is also being investigated for the treatment of agitation in patients with AD who are 65 years and older. The FDA granted BXCL501 breakthrough therapy designation for the acute treatment of agitation in connection with dementia in March 2021, and it has shown statistically significant reductions in agitation with no severe adverse events at doses of both 30 µg and 60 µg.

On December 19, 2022, investigators dosed the first patient in the phase 3 TRANQUILITY III trial of BXCL501. The TRANQUILITY program—which includes 2 investigational studies, TRANQUILITY II and TRANQUILITY III—is designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BXCL501 for the acute treatment of AD-associated agitation in adults who reside in assisted living or residential care facilities and nursing homes. Both trials will enroll about 150 participants 65 years and older with dementia, who will then self-administer 40 µg or 60 µg of BXCL501 or placebo over a 3-month period. Participants will be supervised by a trained research staff member whenever agitation occurs. Full results are expected in the first half of this year.32

Slowing the Progression

Early detection is key to slowing the progression of AD. A recent study found that urinary formic acid is a sensitive marker of subjective cognitive decline that may indicate the early stages of AD. Investigators specifically analyzed the relationship between urinary formic acid and the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene, which confers elevated risk for AD. A noninvasive, inexpensive urine test for formic acid could help improve the rate of diagnosis, which often comes too late for effective treatment.33

Another potential way to detect AD that is relevant to psychiatric clinicians involves depression. According to recent research, individuals with depression are at greater risk of developing late-onset AD, suggesting that treating depression may delay AD development. Although further studies need to confirm and replicate these findings, using polygenic risk scores to predict these diseases demonstrates an advancement in the understanding of the underlying heterogeneity of depression in late-onset AD.34,35

“Thanks to remarkable advances in medical technology, we are all living much longer than ever before. The problem is that our brains were not engineered to live that long. By the time we reach mid-40s or 50s, our cognition begins to slip and it only worsens. That age-related cognitive decline is the precursor of what develops into AD, and we have learned over decades of study that one of the best strategies is early detection and prevention,” said Small. “We have tools now to detect problems early. We have strategies to stave off cognitive decline [that can] have an impact on people’s lives. But we need to do more.”

With growing attention in the media, the US Congress is looking to provide aid. A group of senators recently introduced 2 bills that would renew and strengthen AD prevention and treatment. The first bill, the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) Reauthorization Act, would reauthorize NAPA (established in 2011) through 2035 and modernize the legislation to reflect strides made in understanding AD, such as including a new focus on promoting healthy aging and reducing risk factors. The second bill, the Alzheimer’s Accountability and Investment Act, would require the director of the National Institutes of Health to submit an annual budget to Congress that estimates the cost necessary for achieving NAPA’s research goals.36

Senator Susan Collins (R, Maine), a founder and cochair of the Congressional Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease, released a statement concerning the proposed legislation: “The 2 bills we are introducing will maintain our momentum and make sure that we do not take our foot off the pedal just as our investments in basic research are beginning to translate into potential new treatments. We must not let Alzheimer disease define our children’s generation as it has ours.”36

Quality of Life

Organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association are excited by new prospects in the AD field, particularly when it comes to improving quality of life. “New FDA-approved treatments taken in the early stages of Alzheimer disease could allow people more time to participate in daily life, remain independent, and make future health care decisions. They may create the ability and opportunity to participate fully in important events, such as a wedding, graduation or baptism, a bar/bat mitzvah, or quinceañera,” said Carrillo.

Psychiatric clinicians should remind their patients to address modifiable risk factors: exercise program, diet, stress levels, and social life. Small recommends encouraging patients to take family walks, socialize, modify their diet, and even consult physical trainers. More importantly, he wants everyone to work against a true inhibitor of meaningful life for patients with AD: stigma.

“I think there is still tremendous stigma about the disease,” said Small. “A lot of people are resistant; they come in because of fear and they will minimize their symptoms. It is important to put that in perspective and to help destigmatize this experience.”

Concluding Thoughts

There is a long way to go in the battle to defeat AD. These drugs are the first steps, not the finish line.

“It is incumbent on us to provide realistic and appropriate perspectives to caregivers, patients, and the general public,” said Horacio A. Capote, MD, medical director of the Division of Neuropsychiatry at Dent Neurologic Institute in Amherst, New York, and Neuropsychiatry Section Editor for Psychiatric Times™. “We must do so with the best science we have at our disposal. Various treatment modalities have certainly sowed the seeds for hope. At the same time, we must protect the vulnerable from commercial predation. At the end of the day, we must never lose sight of our humanity.”

References

1. 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(4):700-789.

2. Perry G. A skeptical look at aducanumab. Psychiatric Times. June 16, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/skeptical-look-aducanumab

3. Update on FDA advisory committee’s meeting on aducanumab in Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Biogen. November 6, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/update-fda-advisory-committees-meeting-aducanumab-alzheimers

4. FDA grants accelerated approval for Alzheimer’s drug. News release. FDA. June 7, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-drug

5. Sinha P, Barocas JA. Cost‐effectiveness of aducanumab to prevent Alzheimer’s disease progression at current list price. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12256.

6. Arthur R. Biogen halves price of Aduhelm in the US. BioPharma Reporter. Updated March 7, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.biopharma-reporter.com/Article/2021/12/21/Biogen-halves-price-of-Aduhelm-in-the-US

7. Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Aβ protofibril antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):80.

8. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21.

9. Macmillan C. Lecanemab, the new Alzheimer’s treatment: 3 things to know. Yale Medicine. January 19, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/lecanemab-leqembi-new-alzheimers-drug

10. Couzin-Frankel J. Alzheimer’s drug approval gets a mixed reception. Science. 2023;379(6628):126-127.

11. Arthur R. Next steps for lecanemab: Eisai reveals pricing, US and global rollout plans. BioPharma Reporter. January 10, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.biopharma-reporter.com/Article/2023/01/10/Next-steps-for-lecanemab-Eisai-reveals-pricing-US-and-global-rollout-plans

12. FDA approves LEQEMBI (lecanemab-irmb) under the accelerated approval pathway for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Biogen. January 6, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-leqembitm-lecanemab-irmb-under-accelerated-approval

13. Razay G, Wilcock GK. Galantamine in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(1):9-17.

14. Kalola UK, Nguyen H. Galantamine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. National Library of Medicine. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574546/

15. Galantamine. GoodRx. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/galantamine

16. Patel PH, Gupta V. Rivastigmine. In: StatPearls [Internet]. National Library of Medicine. Updated July 19, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557438/

17. Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Webb AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):211-225.

18. Rivastigmine. GoodRx. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/rivastigmine

19. Kumar A, Gupta V, Sharma S. Donepezil. In: StatPearls [Internet]. National Library of Medicine. Updated December 22, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513257/

20. Donepezil. GoodRx. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/donepezil

21. Adlarity. Prescribing information. Corium; 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/212304s000lbl.pdf

22. Adlarity. GoodRx. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/adlarity

23. Cummings J, Lee G, Nahed P, et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12295.

24. Alzheimer’s Association statement on gantenerumab phase 3 topline data release. Alzheimer’s Association. November 14, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.alz.org/news/2022/statement-gantenerumab-phase-three-results

25. Lilly announces topline results for solanezumab from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trials Unit (DIAN-TU) study. News release. Eli Lilly and Company. February 10, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-announces-topline-results-solanezumab-dominantly-inherited

26. Lilly shares positive donanemab data in first active comparator study in early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Eli Lilly and Company. November 30, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-shares-positive-donanemab-data-first-active-comparator

27. Anavex 2-73 (blarcamesine) phase 2b/3 study met primary and key secondary end points. Anavex. News release. December 1, 2022. February 3, 2023. https://www.anavex.com/post/anavex-2-73-blarcamesine-phase-2b-3-study-met-primary-and-key-secondary-end points

28. Blarcamesine hydrochloride, what is the likelihood that the drug will be approved? Pharmaceutical Technology. January 2, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/data-analysis/blarcamesine-hydrochloride-what-is-the-likelihood-that-drug-will-be-approved/

29. Herrmann N, Wang HJ, Song BX, et al. Risks and benefits of current and novel drugs to treat agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022;21(10):1289-1301.

30. Axsome Therapeutics announces AXS-05 achieves primary end point in the ACCORD phase 3 trial in Alzheimer’s disease agitation. News release. BioSpace. November 28, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/axsome-therapeutics-announces-axs-05-achieves-primary-end point-in-the-accord-phase-3-trial-in-alzheimer-s-disease-agitation/

31. Ward K, Citrome L. AXS-05: an investigational treatment for Alzheimer’s disease-associated agitation. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2022;31(8):773-780.

32. BioXcel Therapeutics announces first patient dosed in TRANQUILITY III phase 3 trial for acute treatment of agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. News release. BioXcel Therapeutics. December 19, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://ir.bioxceltherapeutics.com/news-releases/news-release-details/bioxcel-therapeutics-announces-first-patient-dosed-tranquility-0

33. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhu J, et al. Systematic evaluation of urinary formic acid as a new potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1046066.

34. Upadhya S, Liu H, Luo S, et al. Polygenic risk score effectively predicts depression onset in Alzheimer’s disease based on major depressive disorder risk variants. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:827447.

35. Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(5):532-539.

36. Senator Collins, bipartisan colleagues introduce bills to bolster Alzheimer’s research. News release. Susan Collins. January 31, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.collins.senate.gov/newsroom/01/31/2023/senator-collins-bipartisan-colleagues-introduce-bills-to-bolster-alzheimers-research

Newsletter

Pharmacy practice is always changing. Stay ahead of the curve with the Drug Topics newsletter and get the latest drug information, industry trends, and patient care tips.