Apetamin Gains Popularity on Social Media as Weight Gain Drug

Apetamin has been promoted worldwide as a weight gain supplement—but what are the dangers of misuse?

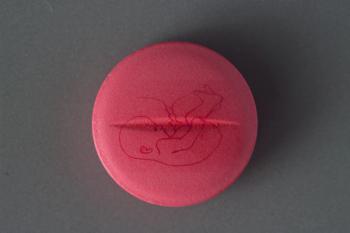

Apetamin, produced by Indian pharmaceutical company TIL Healthcare PVT, is a syrup consisting of cyproheptadine, L-lysine, and B vitamins (dexpanthenol, nicotinamide, thiamine, and pyridoxine).1 While cyproheptadine is available by prescription only in the United States,2 Apetamin syrup is being sold illegally on social media platforms, as well as other online sources, as an unregulated weight gain supplement.3 It has gained attention in the popular media over recent years, with social media influencers promoting its use as a supplement for body enhancement, promising an hour-glass figure that has been described by UK National Health Service (NHS) officials as “unobtainable and biologically unsafe.”3

The misuse of cyproheptadine as a figure enhancer is occurring on an international scale. A 2019 case report from India describes a man who gained 15kg of weight over a 1-year period while taking a “gym-tonic” pill composed of cyproheptadine and dexamethasone, illicitly prescribed by his gym instructor for weight gain purposes.4 Another recent study from the Democratic Republic of Congo describes the “C4 Phenomenon”: In Kinshasa, cyproheptadine is sold as an appetite stimulant under the name “C4” and promoted as a way to obtain a rounded physical appearance.5 More than two-thirds of the population surveyed reported using C4 over the past 6 months, with use found to be more common among women and those with lower educational levels.5 Almost half of users reported that it had been recommended to them by their friends, and over 90% reported self-prescribing.5

NHS leaders in the United Kingdom have urged social media platforms such as Instagram to shut down accounts promoting or selling Apetamin, given significant concerns about its potential physical and mental health effects, particularly for the young women and girls, to whom such content is predominantly targeted.3

Cyproheptadine: A Review

Cyproheptadine is a first-generation antihistamine with antiserotonergic, anticholinergic, and sedative properties.2 It has been in medical use since the 1960s and is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States in the treatment of various allergic conditions.2,6 In the 2000s, it was studied for its orexigenic effects in undernourished children, with variable results.6 It has been used as an off-label treatment for a wide range of psychiatric conditions, to include serotonin syndrome, akathisia, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-induced sexual dysfunction. It has also been investigated for possible use in the treatment of nightmares in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia secondary to stimulant use, behavioral control in autism spectrum disorders, and neuropsychiatric sequelae of efavirenz.7

Safety Concerns

A retrospective review of the French National Pharmacovigilance Database by Bertrand et al examined all reported adverse effects of cyproheptadine since its first distribution in France in 1985, and concluded that it can be considered a “safe” drug.6 Over this 35-year period, there were a total of 93 adverse effects reported, which were primarily neurological and hepatic in nature, with drowsiness representing the most common effect; hepatotoxicity was found to be uncommon.6

The suggested initial dosing for the treatment of FDA-indicated conditions is 4 mg 3 times daily for adults, 4 mg 2 to 3 times daily for ages 7 to 14 years, and 2 mg 2 to 3 times daily for ages 2 to 6 years.2 In comparison, the manufacturer’s suggested daily dose of Apetamin contains 2 mg of cyproheptadine.1 It is important to keep in mind, however, that individuals using illicitly obtained Apetamin as a weight gain supplement may not necessarily be adherent with these dosing recommendations. One case report from 2020 describes a woman who reported drinking Apetamin syrup directly from the bottle in an effort to maximize its reported figure-enhancing effects; after 6 weeks of daily use, she developed autoimmune hepatitis.8

Additionally, given that the illicit sale of Apetamin on social media is inherently unregulated, buyers cannot be certain that the product they are receiving is consistent with the formula reported by the manufacturer, or that the product has not been adulterated with other substances. Consumption of unknown quantities of Apetamin presents the risk of unintentional cyproheptadine overdose. The maximum daily dose of cyproheptadine is not to exceed 0.5 mg/kg per day for adults, 16 mg for ages 7 to 14 years, and 12 mg for ages 2 to 6 years.2

In overdose, cyproheptadine may cause central nervous system (CNS) depression and sedation, as well as anticholinergic syndrome, with symptoms such as dry mouth, dilated pupils, and flushing.2 A 2011 review of the characteristics of intentional cyproheptadine overdoses indicated that around 40% of cases were asymptomatic, while 17% developed anticholinergic delirium, which presented as acute psychosis.9 The average dose ingested was lower for asymptomatic patients than for patients who developed delirium, at 49.8 mg and 188 mg, respectively.9

In addition to the risks described above, the weight gain associated with Apetamin use also presents a risk of developing obesity, which is in itself a risk factor for a range of health conditions including hypertension, type-2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and osteoarthritis.5

Clinical Considerations for Providers

Given that Apetamin misuse is occurring on a global scale, it is important for providers worldwide to be aware of the risks it presents so that they are prepared to appropriately counsel patients. As influencers on social media platforms appear to be predominantly targeting young women and girls in their promotion of Apetamin, awareness is particularly important for providers treating children and adolescents.

Although the study from Kinshasa suggests that potential risk factors for use include female gender and lower educational levels,5 further research is needed into what other factors may place someone at greater risk for use. Providers may wish to consider screening patients with a known history of eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, or other body image-related concerns—particularly patients who are known to use social media platforms. Providers may also simply consider including Apetamin in their routine questioning of young women about medication and herbal supplement use.

In addition to the risks described above, providers should also keep in mind that, for patients who are prescribed monoamine oxidase inhibitors, cyproheptadine has the potential to prolong anticholinergic effects.2

Dr Betterly is a resident physician in the Department of Psychiatry at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Barghini is an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry and behavioral science and director of the Psychiatry Residency Program in the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

References

1.

2. Cyproheptadine [package insert]. Sellersville, PA Teva Pharmaceuticals USA; 2009.

3. Murdoch C, Powis S, Wallace K.

4. Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH, Bawaskar PH.

5. Lulebo AM, Bavuidibo CD, Mafuta EM, et al.

6. Bertrand V, Massy N, Vegas N, et al.

7. Badr B, Naguy A.

8. Garland V, Kumar A, Theisen B, Borum ML.

9. Chu FK.

Newsletter

Pharmacy practice is always changing. Stay ahead of the curve with the Drug Topics newsletter and get the latest drug information, industry trends, and patient care tips.